Inertia isn’t normally a common issue in games with similar time-loop mechanics (see Zero Escape or GrimGrimoire), which means the fault lies squarely with the developer’s bland choices. Given how poorly defined everything is throughout The Path of Destinies, the toughest part of the binary decision between pursuing a recently unearthed artifact or saving an old friend is mustering up enough energy to care about it at all. In fact, a few of the secret scrolls found scattered across each island seem to contradict the game’s plot. There’s nothing particularly memorable about Reynardo, the reluctantly heroic fox that players control, and the overt storybook narration doesn’t have time to delve into what motivates his rival, the evil frog emperor Isengrim the Third, or his love interest, Isengrim’s adopted daughter, the stray cat Zenobia. No wonder The Path of Destinies leans so heavily on pop-culture references (”’Rosebud,’ he said to no one in particular as he died” and “She can do the Kestrel Run in 12 furlongs”), as they help to distract from the relative emptiness of the gaming experience. Granted, each playthrough tells an ostensibly different story, but there are really only four main endings atop the same basic plot, padded out by another 20 or so minor variations throughout. The supposed hook of the game is that the choices made throughout each hour-long playthrough lead to different endings, but even the most inflexible children eventually grow weary of the same book. (For instance, they might think of Bastion, where the on-the-fly narrative matched both the actions of the player and the world springing to life around them.) Here, the storyteller sounds tired from the get-go, struggling to juggle the voices for each character and to strike a balance between try-hard comic quips and the dark tone of the plot, which opens with the casual murder of a young rabbit and frequently ends with the entire kingdom of Boreas being torn apart.

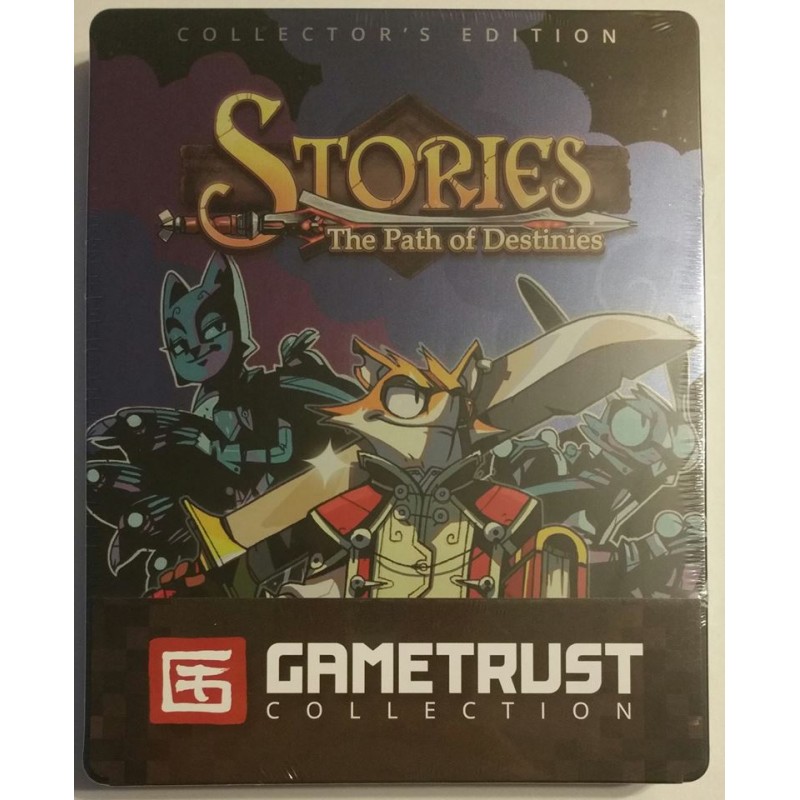

Stories: The Path of Destinies falls into the latter camp, with repetitive gameplay that seems designed to knock players out, where they can, perhaps, dream of a better game. The best bedtime stories for children are those that are entertaining, while the best bedtime stories for parents are those that put children to sleep.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)